FREDRICK WILLIAM PARKER

ENGINEER and VICTORIAN ENTREPRENEUR.

ROSEDALE WORKS,

HUNMANBY.

1861-1934

by

Ces.Mowthorpe. Copyright 2006

Mr William Parker was a tenant farmer on the Hunmanby Estate farming that excellent farm called Graffitoe, with its fine views across Filey Bay. On 1st April 1861 his wife Eliza bore him a son, an only child, christened Frederick William (believed actually born at Hutton Cranswick). He grew into a young man who helped on the family farm, despite suffering from an asthmatic condition. However, Frederick was not cut out to be a farmer. From his earliest years, he was fascinated by everything mechanical – as a teen-ager he equipped one of his father’s buildings into a creditable engineer’s shop, with lathe, drill, furnace etc. and trained himself to work to engineering standards. He built himself a bicycle and repaired any of the rudimentary machinery on the farm. A scholar, he read every possible book or magazine on this subject and spent several months at an engineering works in Hull. It soon became obvious that he was a gifted engineer. His greatest delight was when the local blacksmith, young Mr Cooper brought his portable steam-engine and threshing machine up to Graffitoe to thresh the years crop and he could study and even operate the machinery. (Note: a ’portable’ steam-engine was pulled by horses to each location. The later ‘traction-engine’ was propelled by its own steam power.)

Realizing that his son ‘would never be a farmer’, his father (who had always encouraged him) bought Frederick a Fowler of Leeds steam traction-engine and threshing-set for a twenty-first birthday present so that he could set himself up as a steam contractor. When not in use, the outfit was kept on the farm. Soon he had most of the local farmers as his customers and poor Mr Cooper, whose portable needed to be moved by horses took a back seat. Threshing is by nature a seasonable occupation and although he did a limited amount of haulage work, Frederick (who from here on I will call F.W.) studied the (then) new technique of steam ploughing. Steam ploughing was very profitable if the fields were large and reasonably even – as indeed were a lot of the fields on the Hunmanby estate. By placing a traction-engine at either end of the field, a large double-ended plough (with five blades) was propelled up or down. Moving the engines a few yards ‘on’ and another five furrows could be worked. Now Fowler engines could all be adapted for ploughing, so F.W. had his original so converted and bought another sister engine. These two engines were the basis of all his subsequent business and were always known as the ‘big-wheelers’. They had big wheels with broad tyres for working on the softer soil of fields, as well as roads. A point of interest. The last time steam ploughing was carried-out at Hunmanby was in the early 1930’s. As President of ‘The Steam Engineering Society (?) or similar, F.W. demonstrated to younger members the art of steam-ploughing in the field opposite his Rosedale Works, owned by Mr Nichols. Of course tractors were by now available and ploughing was carried-out with these, instead of horses, in the ’normal’ manner.

The Graffitoe farmyard was now well cluttered with two engines, two threshing machines, ploughing equipment etc. and as F.W. required a building to equip with machinery to service them correctly, he bought part of a field from Messrs Whittakers, alongside Hunmanby railway station, adjoining the now sizable brick-yard quarry, operated by Whittakers, with the opposite boundary abutting Bridlington road. Needing bricks to build workshop, F.W. could not see the point of buying bricks from Whittakers. He ‘poached’ a couple of local brick-makers from them and quarried his own from his land adjoining the quarry (brick-hole). His astute business sense was rapidly developing. About this time he decided to marry and once his workshop was built he commenced constructing ‘Rosedale House’ along the roadside – to which he and his bride lived after marrying. Now well into the brickworks business and employing more staff, F.W. Parker sold thousands of bricks to local builders in the area. Having traction engines which could tow wagons, he could deliver onto the sites direct. Other firms could only deliver to the nearest railway station, to be moved onto site by horse and wagon. His bill-heads now proudly claimed:- ‘F.W.PARKER. Engineer and Brickmaker’. About this time he acquired two other Fowler traction engines and as Mr Cooper, the pioneer of steam threshing locally had little work for his portable, F.W. bought it from him and immediately appointed Mr Cooper as his head engine-driver. The portable was put to work in the brickworks driving the paddles in the huge drum which mixed the clay, continuing to do this until the works closed in 1940.

The necessary back-up for four steam-engines and their accessories required a properly-organized engineering workshop equipped with a forge, lathes, steam-hammer, planing machines etc. all of which required a source of motive power. Consequently a powerful steam-engine (stationary) was installed into a proper engine-shed. Threshing-machines were built chiefly of wood, so were the wagons used by the traction-engines for road transport. Hence, a well-equipped joiners shop was added. All this took several years but the end result was arguably the finest equipped heavy engineering establishment between the Humber and the Tees - coastwise.

Many more workers were required to operate these premises and tradesmen from blacksmiths/engineers to wheelwrights/country joiners were employed, mostly from local resources. F.W. encouraged young men to join his works. They all served a wonderful experience as apprentices to their chosen trade (although none were ’entered-apprentices’ which entailed a premium fee and a later formal ‘indenture’). No indenture was ever necessary – any person who served their time at Parkers was accepted and indeed welcomed.

Naturally, as agricultural engineering flourished at the turn of the twentieth century, F.W.Parker became the area agent for every possible machine or lubricant etc. The only such agent in an area bounded by Bridlington, Scarborough and Driffield. Business flourished. Of course, a practical ‘stores’ system had to be set-up and organized. This was left to ‘Uncle John Smith’. John Smith had been the ‘flag-man’ for F.W. since his early days. Recall that until 1904 or thereabouts, any vehicle traveling along Britain’s roads at more than 4 mph required a man to walk in front with a large red flag. This was John Smith’s task. Tragically, whilst flagging the engine and machine down Hitherstay Hill, between Hunmanby and Muston the engine speeded-up, knocking John down and running-over his legs with a front wheel. The Hunmanby doctor was called for and insisted that only amputation of one leg would save John’s life. Placed on the engine, which was disconnected from the machine, he was speeded back to Rosedale House, who alerted by a cyclist that had hurried ahead, had prepared the kitchen table and provided plenty of clean sheets and boiling water. Here the doctor skillfully amputated the leg and patched John up so he could be taken home. Being of stout country stock, John made a full recovery. In those days there was no pension, and what use was a thirty-year old man with only one leg in a village ? After a full recovery, F.W. provided John with a medical false leg and immediately employed him (for the rest of his working life) as storeman. It was a good choice. Intelligent and willing, Parker’s stores were (for their time) a model of efficiency. John, in later years was allowed to employ his nephew Herbert as his assistant. Herbert is alive today in Australia, where is two daughters live, aged 100years (2006) and many time told me of his Parker years. ‘Uncle John’ was no relative of the Parker family but acquired this title after employing his nephew. By the time W.W.1. came and went F.W. was one of the largest employers in the region (about 40 workers) and ideally placed to venture into the age of the motor-car.

According to one of the Journals of the East Yorkshire Local History Association, there were only two ‘manufacturers of motor cars in the East Riding of Yorkshire prior to 1914. One was Armstrong’s of Beverley and the other F.W.Parker of Hunmanby ! No-one can recall this car(s) identity but logically I suggest that F.W. bought an engine, gearbox and wheels thereupon making and assembling a chassis in his workshops for these components. This would easily be within his works capacity.

Shortly after marriage he bought a motor-cycle with a basketwork ‘sit-up and beg’ side-car. A regular attender (at this period) to the Hunmanby Wesleyan Chapel, villagers eagerly awaited Mr and Mrs Parker on this fine machine on a Sunday morning. It was soon superceded by a car.

In 1914 there was no such thing locally as a garage and filling-station. However Parkers kept petrol in bulk and supplied same in cans. Motor repairs were carried-out as required by F.W. and his engineers who treated them as just another job of work. Electrical products were few and far between but one of the young engineers ‘specialised’ in electrics (Ross Fenby). Another young engineer Mr Watson was seconded for substantial periods to Messrs. Blackburns at Primrose Valley who were assembling Blackburn aeroplanes in their hanger there between 1910 and 1912.

From the foregoing it can be seen that F.W. had built a formidable team of engineers skilled in every practice from agricultural machinery, steam engines and motor vehicles. They were called upon to do all manner of work. When Bostock and Woomwells travelling circus and menagerie overturned their lions cage down White Hill near Bridlington, they could not pull the cage upright with their own engines. F.W. was called and the ‘big-wheelers’ with their ploughing winch/tackle and chains soon had things upright. The cage (complete with lions) was carefully towed back to his works were by dint of a bit of overtime, it was roadworthy next day. Likewise, a steam pleasure boat in Bridlington harbour suffered the breakage of a vital engine part at the busiest week-end of the season. Their usual engineers in Hull had closed down for the week-end. They were losing valuable business. F.W. was contacted, the part placed on the next train and by working through the night a repaired part was dispatched back, fitted and the boat was working again on the Sunday evening.

This period saw intensive building work at Scarborough, Bridlington and Filey. Parkers bricks were never intended as an outside facing-brick but extensively used for internal work. The adjoining railway was used but all local firms had there requirements served by traction engine and trailer. Obviously the brickworks were now a major part of F.W.’s business and he was a good business-man who insisted upon prompt payment. Likewise the farming community – which went through a bad patch pre-WW.1 – had to pay-up quickly if they wanted prime attention at threshing-time. Remember the farmer could not get paid for his crops unless they were threshed first. Hence it was important for them to get a slot for early threshing. F.W. had by now four threshing-sets. As a rule, one served the Hunmanby area. Another served Flamborough area, another Speeton and another Burton Fleming/Grindale area. Thus farmers were familiar with their allotted machines and threshing proceeded in an orderly manner. F.W. was a hard taskmaster. He gave a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work and he kept the men on their toes. His works steam-engine had a hooter and it blew at 08.00hrs, 12.00hrs., 13.00hrs and 17.00hrs. Any workmen not inside the gates when the hooter went lost half a days pay. This hooter governed village life in many ways. All manual work stopped when the hooter went at 12.00hrs. and 17.00hrs., restarting at 13.00hrs. in the afternoon. As a school-boy I well remember the teacher being told ‘Hooter’s gone Miss’ – even if the school clock still showed a few minutes to the hour ! About 1910 F.W. bought the ‘Rolls-Royce’ of bicycles, a Dursley-Peterson Spindle Cycle and was in the habit on threshing-days of cycling out to what-ever farms his machines were working and quietly observing what was going-on. Nothing missed his eagle eyes and woe betide those not pulling their weight. You will appreciate that F.W. ran a tight ship and a profitable business. Several other local threshing-sets were bought by local men but they never really got started due to the fact that they were dependent upon F.W. for regular servicing and he did not deal with competitors lightly !

WW.1 saw a massive improvement amongst the farming community and likewise F.W.Parker’s business prospered. Upon his eldest son Lowish attaining the age of 21yrs. F.W. bought him a threshing outfit which he operated as his own ‘business’ within the confines of the business overall. Like his other steam traction-engines, this was a Fowler of Leeds. It was slightly smaller than the earlier models and for this reason alone it was popular with farmers and workmen for entering and maneuvering inside the smaller stackyards. F.W.’s previous traction-engines were all ‘compound’ steam engines. These were more expensive than single-cylinder models but more efficient and economical – a point which an engineer such as F.W. appreciated. The Fowler engine he bought for Lowish was a single-cylinder and as previously quoted, somewhat smaller. Lowish’s engine soon got the unofficial name of ‘Laakle Tyke’ (Laakle being East Yorkshire dialect for ‘little’). F.W.was a stern taskmaster, treating every-one fairly but equally. When Lowish and the ‘Laakle Tyke’ succumbed to a soft grass verge at the bottom of Stonegate, Hunmanby, returning from a day’s threshing, F.W. who was alerted to this calamity by a workman who had cycled up requesting assistance, promptly sent the workman back to Lowish with a pointed message stating :-“You got it like that. You get it out !” F.W. then going home for his tea. Lowish had to return to the works and get another engine and driver to pull ‘Laakle Tyke’ out of the ditch. Such an attitude had a lot to commend it. Herbert Smith who worked for F.W.for thirty years said many times that he never knew of an engineering or allied task which the firm could not solve – and show a profit.

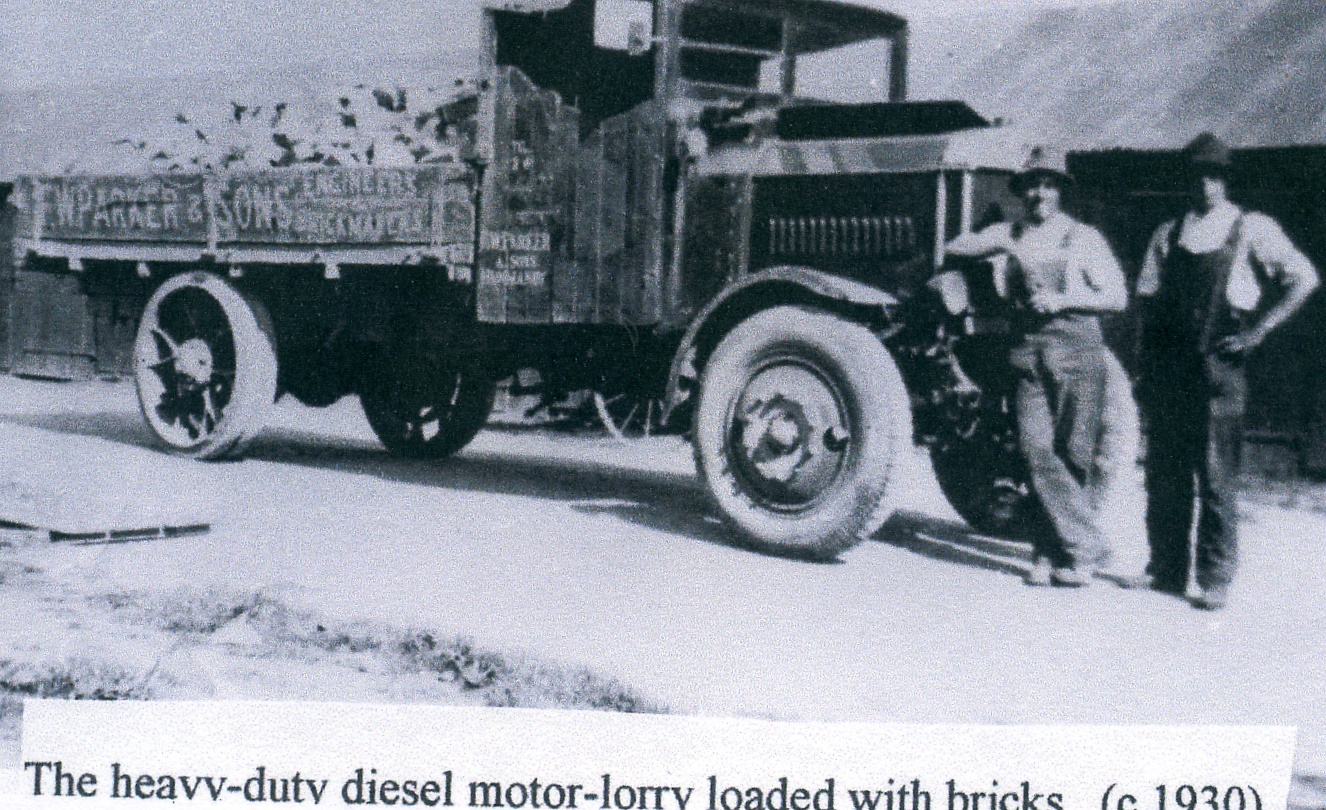

1918 saw F.W.’s eldest daughter Ethel marry Joe German, a young soldier stationed at Hunmanby. The German family farmed at Yaxley, near Peterborough and each year thereafter F.W. and his wife motored down to Peterborough for a fortnight’s holiday each summer. In 1919 this was a formidable task for a motor-car. However, F.W. had purchased a wartime Renault open four-seater, modernized it to his exacting standards and it served the purpose well. Peterborough in 1918 was surrounded by tall chimneys belonging to the London Brick Company which dried their bricks in kilns. This was a much quicker process than the old method of drying the bricks naturally, outside, in the open air as used at Hunmanby by both F.W. and Whittakers. A process which took two years. Being a practical brick-maker, F.W. visited a number of these kilns during his first visit and upon returning to Hunmanby built kilns to dry his bricks. This greatly accelerated his output and a few years later Whittakers, in order to compete had to also build drying kilns. F.W. also bought at an ex-service sale, a brand-new six-cylinder diesel-powered ‘chassis and scuttle’. The works fitted a rudimentary wooden driving cab and substantial heavy-duty flat body on same. It was the first heavy-duty diesel powered vehicle locally and could deliver up to eight-ton of bricks (or anything else) very economically. During the early twenties the Hunmanby brick-hole had a serious landslip which caused the death of two local men working for Whittakers. A now forgotten tragedy which at the time received much publicity. Another landslip, now on F.W.’s section a few years later also had important consequences. It opened up the first complete bronze-age chariot burial to surface in East Yorkshire. Hull Museum sent a team of archaeologists to survey the scene and the remains were moved to Hull Museum. Sadly a direct hit on the museum by a German bomb in WW.2. did away with same and their records. In the 1930’s Whittakers stopped making bricks at Hunmanby and F.W. purchased their works and land for a reasonable figure.

The end of WW.1 saw a surge in automobiles and motor-lorries. F.W. at Hunmanby was ideally placed to add a petrol pump and motor vehicle servicing unit to his works. Filey, an expanding seaside town had an influx of motors, particularly in the summer season. Consequently F.W. purchased a plot of land behind the Crescent and opened the first motor garage in the area – Central Garage – but always referred to locally as ‘Parkers’. It had connections with all leading car-makers and undertook every kind of auto-repair, engine or bodywork. Engineers were interchangeable with those at the Hunmanby works. A rush in summer meant some Hunmanby workers were appended to Central Garage as required. By the 1930’s F.W. was employing up to one hundred local workmen and by far the largest business in the locality. It is to his credit that all the initial motor garages were started by engineers who served their time at Parkers. Examples (now all deceased) are Harry Scott, the Taylor brothers, the Bowes brothers, George Garbutt and Tom and Alf Coates – all to become garage proprietors within the local area.

When his eldest son Lowish married a local farmers daughter Ida White – whose family farmed down the road at Bartindale. F.W. built him a house immediately above Rosedale Works,”Rosedale Villa”, which further added to this industrial complex.

In 1910, an aeroplane hanger had been erected at Flat Cliffs, Primrose Valley, mostly used by Messrs. Blackburn’s (1910-1912) to erect and fly their monoplanes from Filey sands. Used for storage by the Army in WW.1 it came up for sale about 1922. F.W. immediately bought this hanger and dismantled same, with the intention of re-erecting at Rosedale Works to house his traction-engines and threshing machines under cover. Upon careful examination, it was discovered that whilst traction-engines fitted-in, the taller threshing machines did not. F.W. managed to sell this dismantled hanger ‘up North’. About this period, the WW.1. Driffield aerodrome was sold-off by the War Department. F.W. bought one of these hangers, dismantling same and re-erecting at the Rosedale Works after ascertaining It had enough headroom. All manual work was done by F.W.’s staff whatever their trade was. When a job required extra manpower everyone was expected to set to and help.

1921 saw a British submarine, the G3 wash up below Speeton Cliffs. It was being towed to the breakers yard on the Tees. No loss of life was incurred because the tug had taken-off the passage-crew and cut the tow during the bad weather. Hence, a complete WW.1 submarine, less armourments and propellers lay rusting. A local ‘ganger’, with experience salvaging the WW.1. scuttled German fleet at Scapa Flow, one Jack Webster, known to be ‘a dab hand with explosives’ comes into the picture. A fine six-foot-plus man of enormous strength – but no money. He had eyed the submarine up and knowing that it contained two heavy-duty electric generators/motors for its underwater propulsion, approached F.W. with a proposition. He had bought the submarine ‘in situ’, for ’a few pounds’, blown a hatch off with explosives and suggested that F.W. might be interested in buying the two generators to provide his works and houses with electricity. One would be erected at the works and driven by their steam engine, the other providing 100% spares. F.W. realized these generators could be extracted and sectioned – but would still be at the bottom of a 350ft vertical cliff. A shrewd businessman, he agreed to buy providing said generators rested on the cliff-top where his traction-engine and lorry could transport them to his works. Until then no money would change hands ! With the aid of a gin-wheel and rope (borrowed from the Bempton ‘climmers’ Jack Webster and his three teen-aged sons accomplished this feat. Bear in mind that in 1923 Hunmanby had no electricity or gas at all and mains electric light was unknown (it eventually came in 1933). Ross Fenby, Parkers main electrician assembled a generator and wired-up the buildings. Then F.W. had the first truly electric-lighted buildings in the area. It was 24volt DC current but worked excellently until 1953. Successors of Messrs Parkers, who lived in the two houses only changed over to 240 volt mains supply when their wives insisted upon electric washers and televisions !

Following the First World War, many itinerant workers roamed the countryside. Known loosely as ‘tramps’ they sometimes did seasonal work such as harvesting and potato-picking. Traveling either in small groups or singly they slept anywhere they could. Winter was a problem because they were not always welcomed but occasionally isolated barns were ‘made available’ providing nothing was damaged. When F.W. built his drying-kiln for his brickworks, this became a natural night’s stop-over for these ‘knights of the road’. F.W. personally interviewed a large group, telling them that they were welcome each night “after the hooter had gone and providing they had evacuated (without damage) the premises prior to the 08.00hrs hooter”. These men greatly respected this privilege. Mentioned earlier, F.W. suffered from an asthmatic complaint. Later in life it was his custom to walk through his brick drying kiln in the evening – the suphuric fumes given off from the burning coke ensuring a good nights sleep. Naturally he came into contact with these ‘itinerants’ who treated him as one of their own which was a rare privilege. On hearing of his death a deputation of ’tramps’ asked the family if they and their friends could walk behind the cortege between the church and the cemetery. Their request was politely refused.

Fredrick William Parker died on 1st August 1934 aged 73years. This quite brilliant Engineer and Entrepreneur who rose from a farmer’s boy to arguably the premier son of the village of Hunmanby had one grave flaw – he kept tight control of his business to himself. Never introducing his two sons into ‘business’, he would rather see them working hard within its boundaries. His untimely death left them unprepared for the future. Striking unsuitable clay in ‘brickhole’ was a serious problem. Likewise the terrible recession of the late 1930’s which hit the local farming community very badly, causing farmers to be unable to pay their bills (the cost of producing their products was not equalled by any payments they received) and consequently the firm was forced to close down in 1940.