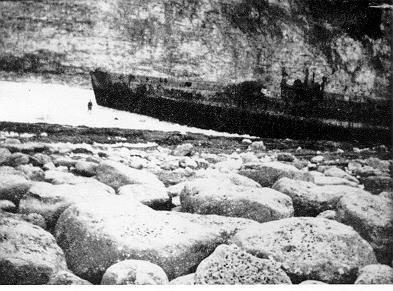

SUBMARINE G.3

FINALLY AGROUND BENEATH SPEETON CLIFFS

1921 found many of His Majesty’s wartime naval vessels being sold for scrap. One such was H.M.Submarine G.3. A firm from the north-east bought the submarine and proceeded to tow it northwards up the North Sea. The vessel was towed ‘awash’ because this was the practical method and had a passage crew of three crewmen on board.

Off Scarborough, a storm blew-up and the passage crew were taken off, the tow was slipped and the following day the submarine washed-up on the North beach at Scarborough, just opposite where the Corner Café (see photo.) stands today (2005). Three days later G.3 was successfully pulled off and the tow resumed.

With Whitby on the port beam, further rough weather led to the tow being slipped again – this time the rogue submarine came ashore upon the rocky bar in Cayton Bay. Re-floated a few days later she again proceeded northwards. Now a real north-easterly gale set in. Well north of Whitby they again slipped G.3. This time they lost sight of her and for three days she was adrift, unmanned, in the busy north sea passage. The following morning the submarine was sighted by Filey coastguards who thought she was drifting onto Filey Brig. However, sliding past the end G.3 drifted across Filey Bay to her final resting-place on the white rocks below Speeton cliffs.

The crew of the tug examined the vessel and with their expert knowledge, decided she was ‘best left where she lay’ so they departed, claiming the insurance! We now have a complete submarine, except for armaments and propellers residing on the White Rocks. All hatches had been secured by the passage crew so no water entered the hull. Despite extensive pounding by the seas, her strong submarine hull prevented any breaking-up. It was possible to walk along to the submarine at certain times but only for very limited periods due to the tides.

Now enter a remarkable man, Jack Webster. A true ganger of the old school, six foot two of pure muscle. He had for the last two years been involved with the salvage of the scuttled German Fleet at Scapa Flow where his knowledge of explosives came in useful. Jack Webster always had an eye for business. He had viewed the submarine with enthusiasm but lacked capital for such a venture. Finally, he approached Fredrick William Parker, a local business-man who had an extensive engineering complex at Hunmanby together with two detached houses. His idea was that by selling F.W.Parker the two large generating motors from the submarine (submarines ran on electric power when submerged),one (with 100% spares) could be driven by the Parker work’s steam-engine and supply both workshops and houses with electric light. It must be noted here that Hunmanby did not get mains electricity until 1931 – nearly ten years after this offer was made. Mr Parker agreed that the idea was excellent but being an astute businessman he insisted that the electric motors were brought to the top of the 300ft Speeton cliffs (in sections) before any money would change hands!

Jack Webster was a practical man. He bought the submarine in situ from the insurance company for “a few pounds” and with the submarine listing on her port-side he blasted his way down through the conning-tower and promptly blew out the port side of the hull. This enabled him to dismantle the electric motors and by using rollers, detach them and get them to the base of the cliffs. He was often assisted by his three teen-ager sons, like him strong and fit. Now the problem was to raise said motors to the top of the sheer 300ft cliff-face. Borrowing the “climmers rope” which was used in the season by the Bempton “climmers” to take rare birds eggs from the nests on the cliff-face, he obtained a gin-wheel which he secured to the cliff-edge then hired a horse from a friendly farmer for two days and promptly lifted the motors to the top of the cliffs. Here Fredrick Parker sent one of his traction engines with trailer and the deal was done.

Now with a little capital, Jack bought an old pulling boat for five pounds and spent every available opportunity at the submarine, stripping all valuable ‘scrap’ such as copper, brass etc. At this period such material was fetching a good price. Eventually he sent a whole railway-truck load to West riding merchants, thereby showing a healthy profit. Now, stripped of her valuable items, the G.3 was left, like stranded whale, to rot away. So strong was the submarines pressure-hull that she remained a visual item until 1940 when the military blew-up all recognizable landmarks in a effort to confuse ‘an invading force’. However, the writer flew extensively over this area and up to the 1960’s, the skeleton outline of G.3’s ribs and keel were visible from the air.

Meanwhile, with his profits, Jack Webster bought a small wooded copse known as Airey Hill alongside the A.165 opposite the old Butlins Camp-site. Here he eventually built and sold ten bungalows, retiring in one – from the proceeds of H.M.Submarine G.3.

G.3’s electric motors continued to light up the Parker Works and the two houses (although these changed hands) until the early 1950’s. Although still working perfectly, the female tenants of the houses demanded such modern delights like electric washing machines and television!

As such did not operate on 24v.DC the system was scrapped and mains electricity (240v AC)installed.

Visiting Greenwich Naval Museum in the 1970’s, the writer requested information upon this submarine wrecked below Speeton. He was met with polite but absolute refusal to believe that such a wreck had occurred. The friendly curator promised to look further into this matter. Two weeks later he telephoned me and announced he had solved the problem. No official record of this ‘wreck’ existed. However, as an insurance company was involved he managed to establish that it was definitely H.M.S.G.3 but it was not recorded anywhere as a ‘wreck’. That is, because G.3 washed up on it’s own accord during a storm – hence it was flotsam !

Ces.Mowthorpe (Copyright 2005)Photograph supplied by Mr David Howarth.